Researchers asked students at the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) to create new words for 18 contrasting ideas: up, down, big, small, good, bad, fast, slow, far, near, few, many, long, short, rough, smooth, attractive, and ugly. In pairs, the students would guess the meaning of each word based only on their sounds. No bodily gestures or facial expressions could be used when delivering the word to the student who would guess the meaning. The students were successful in guessing the meanings and improved with experience. Analyzing the data, author Marcus Perlman, a cognitive scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and lead author of the study, said the guessers were successful because the inventors consistently used certain types of vocalizations with certain words, linking ideas with acoustic labels.

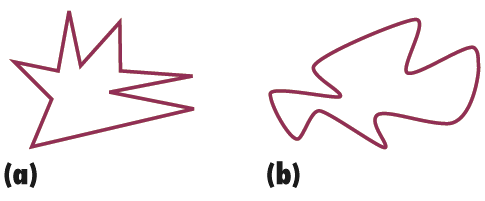

The study was an extension of the Baoba/Kiki effect, which was originally proposed in 1929 and further tested in 2001. The Baoba/Kiki effect examined the relationship between signifier and signified by asking students, one group of English-speaking college students and another group of Tamil-speaking college students, which of the following shapes they would name “Baoba,” and which they would name “Kiki.”

These similar intuitions could simply be cultural understanding. The study was conducted among English-speakers of a similar background. When Perlman ran a similar study in rural China, the results were close, but not identical. Instead of using higher pitches for smaller objects and lower pitches for bigger objects like the English-speaking students did, the Chinese-speaking students did the opposite. Perlman suspects that this is related to the use of high-pitched tones to convey strength and power in Chinese folk performances, showing how cultural influence and already speaking a language hinders the study.

#linguistics #language